Stacking Bricks and Prioritizing Frequency

How Small Efforts Add Up to Big Results Over Time

I signed three new clients last week—a 25-year-old real estate broker preparing for the Chicago Marathon, a 23-year-old former Ivy League football player preparing for 70.3 Eagleman, and a 35-year-old firefighter preparing for the Tahoe 200. Before working with an athlete 1-1 for the first time, they fill out a questionnaire—providing me with their personal information, athletic background, injury history, motivations, goals, and other relevant information.

After reviewing the questionnaire, we get on the phone for a kickoff call—an opportunity for me to answer their questions, walk them through workouts, give them an idea of what to expect, explain heart rate zones, communicate expectations, and share my training philosophies and principles. Here are two:

Stack Bricks

As an athlete, and now as a coach, I’ve come to realize the importance of consistency. It compounds in similar ways an S&P 500 index fund does. Not all growth is linear, but over time, charts tend to go up and to the right. As the late, great Charlie Munger once said, “The first rule of compounding is to not interrupt it unnecessarily.” Shoot for steady.

Not every workout should be a big, intense, or long effort. Most shouldn’t. One of the keys to success in endurance sport is doing enough to stimulate and signal adaptation, but not enough that you cannot recover and suffer consequences later. You want to be able to show up day after day, week after week, month after month, season after season, year after year.

Shyanne McGregor, a Duluth-based pro, has been my coach since 2021. While I grew and greatly improved under Shyanne, there was no magic workout. There was, however, three years of disciplined commitment and consistency to a craft. I would’ve developed under a variety of coaches and methodologies, but the best plan is the one you stick to. Consistently good beats occasionally great. It’s hard to beat someone that doesn’t quit.

When explaining this concept to my coached athletes, I like to use a brick house analogy. If your job was to build a brick house, you’d first extend your time horizon and accept it would take a significant amount of time. There are no shortcuts, no free lunches. Every day, your job is to lay one brick to the best of your ability. It will not be perfect. Perfect is an impossible standard to meet and sets ourselves up for failure.

Some days, the brick will be harder or take longer to lay (i.e. five hour Ironman rides with a tempo run off the bike, followed by a strength workout). Some days, it will be easier, may not look like much, and you get the job done quickly (recovery swim). Others, it’s best for you to stay away from the house completely and focus on other tasks to not jeopardize the work you’ve already put in (rest day). Even on those days, you’re doing your job. You still made a conscious effort toward your goal. Remember, recovery allows our bodies to absorb and benefit from the training stimuli and volume. Stress + rest = growth. Show up, stack your brick, and go home. This is the path for sustainable performance.

Building a brick house, even just a brick wall, is a step-by-step process. If we fail to place one brick in its correct place or order, the subsequent bricks can’t be placed properly and are built on an unstable foundation. However, over time, if placed correctly, we’ll have a strong, robust structure that’s prepared to withstand increasing load and stress. Rome wasn’t built in a day and neither is fitness.

Frequency is King

In his peak, Michael Phelps trained up to 40 hours per week. Ahead of the 2008 Beijing Games, Phelps didn’t take a day off for nearly six years. Christmas, birthdays, didn’t matter. He’s said that for every day he was out of the water, it took him two days to get back to where he was—suggesting he’d gain an extra two days on his competition every week.

When you have a goal that’s important enough to you, nothing will stand in your way…the greats do something when they don’t always want to do them.” - Michael Phelps

I’m by no means suggesting we all follow suit, especially the weekend warriors and bucket list Ironmen, looking to just finish one of these events. After all, this came from the most decorated Olympian of all time, a merman who was known to log 100k weeks in the pool. However, even the Average Joe can modify and apply the principle he’s alluding to—frequency is king.

This is also a lesson I’ve learned from Gordo Bryn, the OG endurance blogger. He regularly does short, easy frequency runs as a way to build fitness and durability. I incorporated these during my Ironman Texas and Kona builds— running after almost every ride, even if just for 20 minutes. Three frequency runs off the bike is another hour per week, so don’t knock it. It all adds up. He applies the frequency principle to swimming too by “touch[ing] the water.” Some days he swims 5k. Others are much shorter, but the important thing is that he got in the water that day. Something is almost always better than nothing.

Once you’ve proven you can swim, bike, and run multiple times per week, we increase the duration, and finally the intensity. If you can’t show up for a 45 minute aerobic ride, I’m not going to give you a three hour session with 4x4 intervals at best sustainable effort to boost your VO2 max. You likely need more base, not intensity, but that’s a topic for a future heart rate training post.

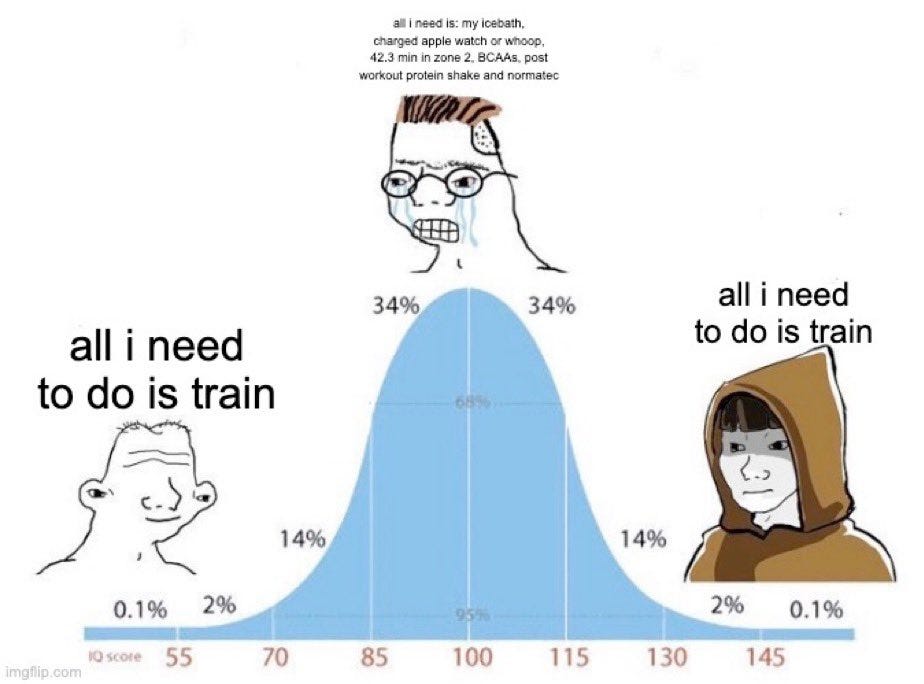

What got you here won’t necessarily get you there, but most of the time, greatness comes from doing the unexceptional, boring basics for an exceptional period of time. Don’t talk to me about cold plunges, beef liver, or red light therapy until you’re moving daily, fueling your mind and body with a nutrient-dense foods, and getting adequate, quality sleep. Don’t major in the minors.

Tony Robbins made a recent appearance on my favorite podcast, Modern Wisdom. In that episode, he shared his experience working with NBA all-star Steph Curry. We see Curry effortlessly swish threes from half-court, being named scoring champion, and crowned MVP. What we don’t see is what goes on behind the scenes—a minimum of 500 shots a day, every day. That’s 3,500 a week, 182,500 a year, 2,737,500 in his 15 years as a professional, all in practice, in empty gyms. Yes, AI, we talkin’ ‘bout practice. We get rewarded in public for what we practice in private.