Over the past few months, I’ve shared several of my coaching principles—like stacking bricks, prioritizing frequency, the rule of thirds, and holding your egg loosely.

Today, I want to explore another topic that’s central to success in endurance sport: training zones.

Zones are top of mind for me because I started working with two new clients last week. Lorraine and Shelby are both endurance beginners and I shared the importance of heart rate training with them on our first call.

The Importance of Heart Rate Training

Perhaps you were a varsity letterman in high school, maybe even in college, but let life get in the way. As a result, the lean physique and vibrant energy you had in your early twenties are things of the past.

Motivated by seeing your friend from college complete a half marathon, or David Goggins’ appearance on The Joe Rogan Experience, you lace up your running shoes after an extended hiatus.

And you go out at the same pace you ran the mile during the Presidential Fitness Test well over a decade ago. And you get injured and feel defeated.

After months of physical therapy, you do some research and come across zone training. Or you start working with a coach who prescribes training by heart rate.

Excited again, you go out for an “easy run” and as soon as you go from a walk to a jog, your heart rate goes through the roof. Sound familiar? You’re not alone. I’ve been there. We’ve all been there.

When I started my triathlon journey in 2019, I walked a lot, especially up hills, to prevent my heart rate from spiking and staying there. As a result, my pace for most “runs” would be around 11:30-12 min/mi. Not fast, but I trusted the “slow down to speed up” process, as tedious as it was, kept my Strava private to remove the peer pressure, and gained endurance. Six years later, I run around 7:15 min/mi at the same heart rate and perceived exertion, and can do so for hours.

Attia’s Pyramid

If I haven’t yet convinced you to pay attention to heart rate, let me convey its importance using pyramid or triangle analogy I learned from Dr. Peter Attia.

If the triangle represents your cardiovascular fitness, the bottom of the pyramid is your aerobic base. When we engage in aerobic exercise, we use oxygen to produce energy for sustained activity. When moving at these lower intensities, we primarily burn fat for fuel. The more time you spend developing your aerobic system, the wider your base and the more efficient you become.

The wider the base, the higher and sharper the point at the top of the pyramid can be. The peak of the pyramid is your top end—your VO2 max, the maximum amount of oxygen your body can use during intense exercise. When our cells don’t get enough oxygen at this intensity, we break down glucose (sugar) for energy and produce a chemical called lactate. As exertion and duration increase, we use more carbohydrates to keep going.

For most, the goal is to maximize the area of the triangle. And in order to have a taller, stronger structure, we must start by building a wider base. Think of it this way—you can’t build a roof of a house without a solid foundation beneath it.

The Five Zone Model

There are different models, but the most common seems to be the five zone model. Here are two great resources from endurance legends,

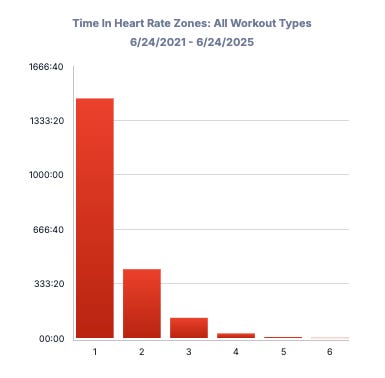

1 and :As you now know, these zones are based on subjective feeling or rate of perceived exertion (RPE), as well as heart rate, specifically percentage of maximum heart rate.

People tend to use the formula 220-age to determine max heart rate, but as with any generalization, there are outliers and flaws.

To get an accurate reading of your maximum heart rate, Gordo suggests you “run or bike up a hill for 4-6 minutes in zones 4-5, and when you feel you can’t go on much longer, put in an extra effort (sprint). Look at your heart rate monitor before you keel over; that is your maximum heart rate.”

Unfortunately, there’s not an objective truth or consensus out there on zones. People define them differently; however, zone 2 is commonly said to be ~70% (can range from 65-80%) of max HR.

Phil Maffetone popularized the MAF 180 formula. To find your aerobic threshold, he suggested subtracting your age from 180. Do most of your training below that number.

Zone 1 and 2 training lays the groundwork that supports your higher intensity work. Over time, you will run or ride at the same speeds with less effort.

Zone 2 purists swear by the “run slow to run fast” mantra. While there is some truth to that and it does improve vascular health, fat oxidation, and mitochondrial content, it’s not the only training in a well-balanced program.

While zone 3 and 4 efforts are often dismissed as “junk miles” in the “gray zone”, I believe they serve a purpose. These tempo and threshold intensities simulate race pace. These “happy hard” or comfortably uncomfortable sessions raise your high-end ceiling.

And then there’s zone 5, close to our maximum output and effort. Polarized training—the idea we should spend 80% of our time in or below zone 2 and 20% in zone 5—has become quite popular, especially in the world of elite performance.

For world-class athletes like Tour de France riders training 30-40 hours/week, that might be even closer to 90/10, but that’s not the new runner or weekend warrior, never mind the average person. The less you do, the less trained you are, the more likely you are to drift into higher zones, and that’s okay.

When riding, I recommend subtracting 10 bpm from these zones. Cycling requires less muscle recruitment and oxygen, which is why it’s often harder to get our heart rates up on the bike than on two feet.

Exercise physiologist and 2:24 marathoner

2 has noted, a simplified three-zone training model can be effective too:Easy (50-70% HR max)

Moderate (70-85% HR max)

Hard (85-100% HR max)

The Talk Test & The Breath Test

To ensure we’re targeting the “right” zone, I recommend getting a heart rate chest strap or even a bicep band as the sensors on watches tend to be less accurate.

While HR is a helpful metric, it’s just a tool, and an imperfect one at that. The only way to actually ensure we’re targeting the right zone is by taking lactate, which is unrealistic to regularly do, especially for novices.

This is why it’s even more important for athletes to practice going by feel. This is when I introduce two tests to my athletes: the talk test and the breath test.

The talk test—can you maintain a conversation during exercise?

The conversation shouldn’t be the most enjoyable or comfortable to have, but you should be able to converse with a friend you’re sharing miles with or speaking to on the phone. If I don’t run with a training partner or listen to music or podcasts, I often call people during long runs. If not, talk out-loud to yourself. If you can hold a conversation, you’re likely in zone 2 or close. If you can’t, you’re going too hard.

The breath test—can you breathe through your nose?

Unless you have a deviated septum, terrible seasonal allergies like me, or are a lifelong mouth-breather, aim to breathe in and out through your nose. Second best would be to inhale through the nose and exhale through the mouth. Last choice is exclusively mouth-breathing. Huffing and puffing is another sign you’re going too hard.

It’s important to note these subjective tests are to train yourself to go by feel—to get a sense for what your steady state, all-day, endurance pace and effort should feel like.

Acknowledging Complexity and Differing Opinions

As I previously said, the jury’s still out on training zones. There are a few schools of thought on this.

4:01 miler, coach, and author

is of the belief that most people don’t need to worry about the precise zone.Zones help guide and categorize training, but they’re not magical. The boundaries are unclear—think dimmer, not on/off switch. On this spectrum, it’s important to mix in different types of intensities, but the interval work should be controlled.

I agree—if you’re starting from scratch, any training is a stimulus. If we give ourselves time to recover, and have the durability to tolerate the training stress, we will make adaptations and see performance improvements.

Steve’s training poem has always stuck with me:

“Mostly easy, occasionally hard, vary it up, and very seldom, go see God.”

“Do that for months and years, and you'll be fine.”

Exercise physiologist and coach

has a different take—that intensity discipline might be the most important factor to long-term athletic development.Either way, the key is to go easy enough to accumulate volume (time exercising, mileage) consistently. Try to avoid living the upper zones because those carry higher injury risk. Intensity also creates fatigue. If you go too hard and hurt yourself, you’re breaking the first rule of compounding—don’t interrupt it unnecessarily.

Either way, beginners must get fit enough to train…before they train. Build that foundation so you can benefit from the intense work you do. Heart rate still high?Don’t be afraid or too proud to walk. You’re new to running. Why do you believe you should be running 7:30 min/mi? Influencers on Instagram? Do zone 2 intervals—walk-run intervals. Treat it as an interval workout. Reframe walking as zone 1 running.

When in doubt, do more base.

The original title for this post was “Simplifying Zones”; however, as I dug into the topic, I realized how complex and nuanced it is. In a continual effort to learn, I’m leaving this open-ended and open-minded. That’s the beauty of science. I welcome feedback and comments.

Thanks for reading. If you enjoyed this or found it valuable, please subscribe via the button below. It’s an easy, free way to support my writing and coaching.

“The more I learn, the more I realize how much I don't know.”

― Albert Einstein

Here are two great write-ups from Gordo—Zone Basics & Building Athlete Profiles

Great read as a beginner Learned a lot Thankyou

Well, you know how I ♥️ heart rate training. Everything old is new again. Thanks.